Drawing the Other Self: A Backstage Portrait of Chinese Opera.

- Tatiana Mocchetti

- Jun 28, 2025

- 9 min read

Backstage, time slows down. The noise of the outside world fades, replaced by the soft rhythm of brushes against skin, the rustle of silk, and the quiet hum of anticipation. It is in this space — before the music starts and the spotlight rises — that a sacred transformation begins.

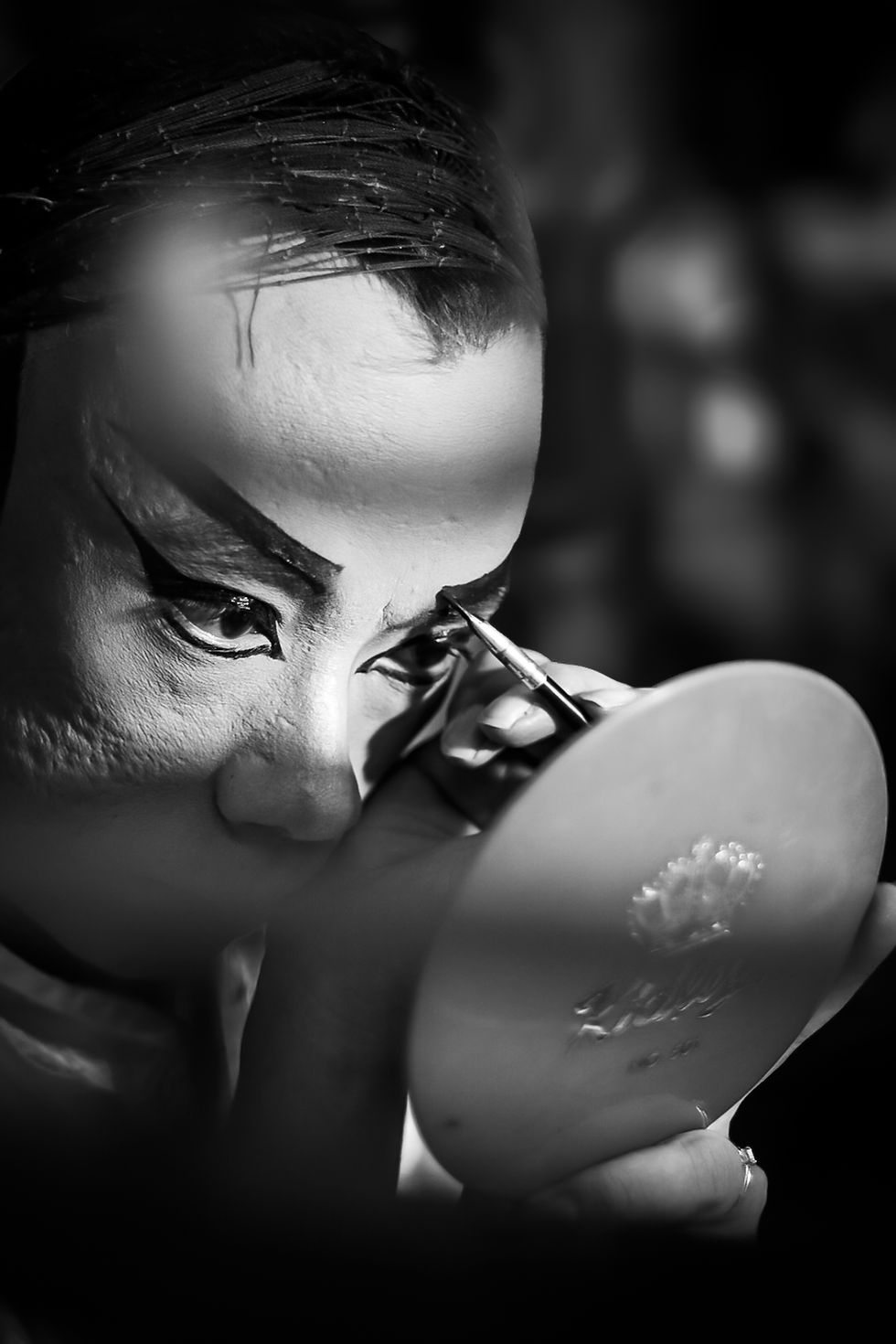

In Chinese opera, a performer doesn’t simply get into character. They become the character, stroke by deliberate stroke. As a photographer, I was drawn not just to the spectacle on stage, but to the quieter, more intimate process of drawing the other self. Watching an ordinary face turn into legend — it was as if I were witnessing the past come alive through each line of makeup.

This post is a glimpse into that space. Into the artistry, the heritage, and the vulnerability behind the performance. And into what it means, as a photographer, to witness tradition in motion — without interrupting it.

1. A Glimpse into Chinese Opera Tradition

Chinese opera is one of the oldest and most visually elaborate performance arts in the world, blending theater, music, acrobatics, and symbolic storytelling. Originating over a thousand years ago, it evolved into many regional styles — from Beijing opera (Peking opera) to Cantonese, Hokkien, and others — each with its own traditions and character types.

In Thailand, Chinese opera lives on through communities of Chinese descent who preserve this cultural heritage. Traveling troupes still perform during local festivals, setting up temporary stages in temple courtyards and market squares. Backstage, the air is thick with incense, paint, and stories passed down through generations.

The makeup is never random. Every color, every brushstroke carries meaning:

White for cunning and villainy

Red for loyalty and courage

Black for strength and integrity

Blue or green for rebellious or fierce spirits

Costumes are richly embroidered, and every gesture is choreographed — a single hand movement can signal joy, defiance, or heartbreak. As a photographer, understanding this visual language helped me frame not just images, but meanings.

But even more fascinating than the performance was the preparation — the becoming. And that’s what this photo series captures: the quiet transformation from self to symbol.

2. Gaining Access with Respect

Photographing backstage at a Chinese opera is not like wandering through a street market or catching candid shots on a public square. It’s entering a sacred, intimate space — one where tradition is alive, but also vulnerable.

I was not invited as a journalist. I was simply there — curious, respectful, camera in hand. At first, I lingered at the edges, observing quietly. Eventually, one of the performers noticed my interest, smiled, and waved me closer. That small gesture opened the curtain to a world not often seen by outsiders.

I did not begin by shooting. I began by watching. By listening. And by asking.

📷 “Tai ruup dai mai ka?” — “May I take your photo?”This phrase, once again, bridged the gap between me and my subject. Some nodded immediately. Some looked unsure. In those moments, I put the camera down. The goal was never to take something — it was to be invited to witness it.

There were no stage managers or media liaisons. Only people preparing for a performance they’d given countless times before — and yet still approached with reverence. The silence backstage wasn’t emptiness. It was focus. Purpose. A collective breath before stepping into myth.

I made it my responsibility to be nearly invisible. To move with care. To photograph from angles that didn’t interrupt. I avoided flash entirely — trusting ambient light to do its quiet work. And in doing so, I found something unexpected: the more I respected the space, the more welcome I became.

In many ways, this wasn’t just a photographic moment — it was a cultural exchange. A mutual understanding. And that, more than any technical setting, made the images possible.

3. Working with Light, Color, and Intimacy

Backstage is not made for photographers. The light is uneven — dim in some corners, harsh in others. Color spills everywhere, from red stage bulbs to fluorescent tubes, sometimes flickering, sometimes too warm. But this chaos is also beauty — raw, authentic, and alive.

To photograph it, I had to let go of perfection.

I brought my 85mm lens, the same one I use for intimate portraits in the street. It’s not the most flexible choice for tight spaces, but it gave me the distance I needed to remain discreet — and the closeness I needed to feel the emotion. That lens allowed me to focus on details without intruding: a brush poised in midair, the glint of sweat near the temple, the shimmer of gold lining a cheek.

I shot wide open, usually at f/1.8 or f/2, to let in as much light as possible. The shallow depth of field softened the chaos around my subject and brought clarity to what mattered. I used no flash. Flash would flatten the mood, break the intimacy. Instead, I embraced the shadows — letting them wrap around the subjects like part of the costume.

When necessary, I nudged the ISO higher, accepting a bit of grain as texture. It added a documentary feeling to the scene — something honest and imperfect.

What helped most was learning to anticipate. When a performer leaned into the mirror, when the brush hovered in stillness — those were the moments I waited for.

And then, color. Chinese opera is a visual feast: saturated reds, emerald greens, inky blacks. It’s theatrical, but symbolic. I didn’t want to oversaturate those hues in post-processing — I wanted them to breathe naturally. The idea was always to stay true to the atmosphere. To let the color carry its weight, as it was meant to.

More than once, I forgot I was taking photos. I was simply watching someone draw the other self, stroke by stroke, with every pigment telling a story older than both of us.

4. The Transformation Process

The calm, the focus, the ritual — and the soul beneath the mask

There’s something sacred about the moment a performer becomes someone else. Backstage at the Chinese opera, I witnessed that transformation not as a spectator, but as a quiet observer with a camera, standing just outside the intimate circle of ritual.

The room was not chaotic. It pulsed with slow, focused energy — like a temple preparing for ceremony. No one rushed. Each brushstroke was deliberate. Each movement, measured. Some performers painted in silence, others whispered lines under their breath or softly hummed melodies from their scenes. Their faces weren’t yet their characters’, but they weren’t quite their own anymore either. They were in between — in the process of becoming.

It was here that I began to understand the emotional weight behind each transformation. This wasn’t makeup. It was mythology coming to life.

I watched an elderly performer meticulously outline the black lines around his eyes — symbols of authority, strength, and wisdom. His fingers trembled ever so slightly, but his eyes were steady, lost in a memory only he could access. Nearby, a younger actor sat barefoot on the ground, surrounded by the tools of his craft — greasepaint tins, faded mirrors, tissue-thin costume instructions. The younger man applied each color slowly, mirroring what he’d seen his elders do countless times.

In these moments, I didn’t just see people getting ready for a performance. I saw a lineage being passed down in pigment and gesture.

What I tried to capture with my lens wasn’t just their faces. It was the moment when the self fades into the role — when identity is suspended. There’s something deeply human in that space: vulnerable, sacred, and surprisingly serene.

And when I later looked through my photos, it wasn’t the final painted faces that struck me most. It was the quiet before. The reflection in the mirror. The pause after a line is drawn. The softness behind the mask.

Because even as they transformed into someone else, the person — the soul — always remained visible, if only for a moment. And that is what I hope lives in the photographs.

5. Cultural Layers Through a Lens

Understanding the stories behind the colors, gestures, and gaze

At first glance, Chinese opera is a visual explosion: crimson and gold costumes, thunderous music, elaborate headdresses, and theatrical gestures. But as I stood behind the curtain, I began to realize it’s more than performance. It’s language. It’s legacy. It’s a coded system of storytelling that predates modern theater, yet still resonates with those who know how to look.

In the traditional opera, characters are not created from imagination alone — they come from centuries of shared narratives. Each role is steeped in meaning:

Sheng (the male lead) embodies righteousness, bravery, or gentleness — depending on the subcategory.

Dan (female roles) may range from youthful innocence to powerful matriarchs.

Jing (painted face roles) are often generals, villains, or spirits, each with unique facial designs signifying their nature.

Chou (the clown) brings comic relief but also delivers social commentary, often masked in humor.

As a photographer, understanding this changed the way I approached my subjects. I no longer saw an actor in a costume — I saw the embodiment of a cultural archetype.

When I captured a close-up of a woman with bold pink eyeshadow and intricate floral embroidery, I wasn’t just photographing beauty. I was documenting a visual symbol of femininity and resilience, a role likely rooted in legend.

When I focused on a Jing role — with his broad stance and sharply painted face — I wasn’t just drawn to the colors. I was drawn to what they meant. The red lines across his brow told me he was loyal. The black over his nose, that he was strong-willed. His wide sleeves weren’t just dramatic — they were narrative tools, meant to enhance movement and emotion.

Costume, gesture, voice — they are all part of the story. And through my camera, I began to understand that I wasn’t just documenting people. I was documenting the survival of oral history, performed through body and paint.

Every time I pressed the shutter, I was translating a cultural moment into a visual one. Not interpreting, not redefining — just holding space for it.

And for those who will view these photos without knowing the opera's meanings, I hope they still feel it: the gravity of tradition, the dignity of performance, the quiet power of symbolism. Because sometimes, you don’t need to understand every word of a language to feel the emotion in the tone.

6. What I Learned as a Photographer

Letting go of control, honoring the space, and being human first

When I entered the world backstage, I didn’t bring a checklist of shots to capture. I brought curiosity. And humility.

In the beginning, I stayed on the edges. I didn’t want to intrude. I observed — not with my camera first, but with my eyes, my breath, and my heart. And slowly, something shifted. The performers allowed me into their rhythm. Not because I asked — but because I respected the space they held.

Photography, for me, has often been about anticipation. Being quick, responsive, ready to frame the moment just right. But here, it was the opposite. This wasn’t about chasing the moment. It was about waiting for it to arrive. And learning to recognize when it did.

I had to learn not just when to take a photo — but when not to. Some moments were too tender. Too quiet. Too sacred. And I knew instinctively they weren’t mine to keep.

This experience reminded me that great photography isn’t only about technique — it’s about presence. It's about how we see, not just what we capture. I wasn’t there to direct or document. I was there to listen — with my lens, but also with my whole being.

Backstage at the Chinese opera, I saw more than faces painted into mythology. I saw generational memory being passed from hand to hand. I saw pride and vulnerability sitting side by side. I saw performers gently guiding one another through tradition — not as artifice, but as inheritance.

And I came to understand that in cultural or sacred spaces, the camera must always come second. Because when we photograph with reverence, when we slow down and let the story unfold on its own terms, something beautiful happens: the images begin to breathe.

They’re not trophies. They’re tributes.

And that’s what I carry with me now — a deeper respect for stillness, for observation, and for the human story that pulses beneath every layer of costume, every line of makeup, every click of the shutter.

Because in the end, the best photographs aren’t just reflections of what we see. They’re records of how we felt when we stood quietly, and let someone else lead the moment.

Comments